Manet vs. Monet, or Unlikely Associations and Analogies from a Visit with the Oncologist

Progress Report

This week I received reassuring and really marvelous news from my oncologist, Dr. John Ward, based on a blood test and an MRI. With Susan at my side he explained that the bilirubin level had decreased once again to 1.9. This means the liver is able to fight back the tumors, keep them in their trenches. The MRI showed no apparent growth in the larger tumors, and there were signs of necrotic (dead) tissue. The overall size of the liver has not increased, but the liver is about twice the size of a normal liver. The large liver size and its invasion of neighboring organs is the primary source of pain that is nobly relieved by the twin siblings: Oxycodone and Oxycontin. At the conclusion of our consultation, Dr. Ward recommended we keep things as they are, so we are not considering other treatments until at least six months from now when I get my next MRI.

Manet vs. Monet

Dr. Ward then shifted to matters not seemingly related to cancer treatment. John congratulated Susan on her appointment as Dean of Undergraduate Education at Brigham Young University. He spoke of how valuable his general education was as an undergraduate, and even remembered a class in mythology that helps him solve crossword puzzles. And as much as he enjoyed his art history class, he was still trying to keep Manet and Monet straight. I suggested that his confusion between the two is probably shared by many, and could give me the opportunity on our blog to tie the problem by association and analogy to the fight against cancer. I surveyed a few friends to get their take on the difference between Manet and Monet, but the best I could get was this: Manet is what you put on sandwiches, and Monet is the longest day of the week!

Seriously, Manet launched his career as a rebellious painter in the atelier of Thomas Couture solidly in the tradition of academic idealism. The critics agreed: Manet could be a great painter if he would stop producing incomplete paintings that clearly revealed the artist’s personal artistic touch. Instead, he should “finish” his paintings under layers of varnish, as was the tradition. A few superlative examples of his paintings include Luncheon on the Grass, Olympia, and The Dead Christ with Angels. His confrontation with the tradition of academic painting drew critical barbs from virtually all reviews in Paris. Yet Manet persisted in his quest for recognition by the National Academy of Arts.

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass, 1863

Eventually he found acceptance in a group of painters who also felt the need to break from the traditions of academic painting. These young painters came to be known as Impressionist, and their movement as Impressionism. Manet became their spiritual guide in part because his work appeared to be like the Impressionists, but actually he differed in fundamental technical terms.

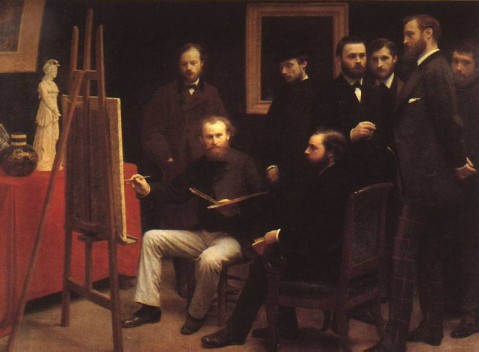

Fantin-Latour, Studio in the Batignolles Quarter, 1870. Manet is seated at his easel surrounded by artists and literary figures including Renoir and Monet (far right).

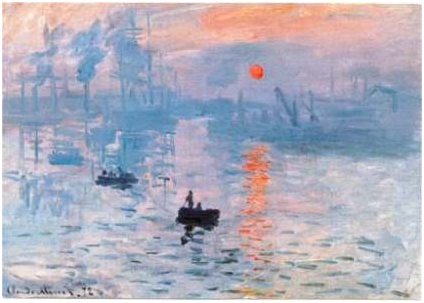

Monet and his group were influenced by the great literary figure Charles Baudelaire, who urged the Impressionists to use their technique to portray modern life in Paris. They depicted the rise of the prosperous bourgeoisie promenading in parks, dining at cafes, attending the theater or opera, and picnicking at the beach. Monet’s garden was a source of inspiration until his dying days. His painting Impression Sunrise depicting the harbor at Le Havre gave critics a facetious name for the group that by century’s end was an accepted form of painting.

Claude Monet, Impression Sunrise, 1872

Manet and Monet both painted bourgeois tourists at the seashore at the advent of Impressionism: On the Beach at Boulogne by Manet; and The Beach at Sainte-Adresse by Monet.

Manet, On the Beach, Boulogne-sur-Mer, 1868

Monet, The Beach at Sainte-Adresse, 1867

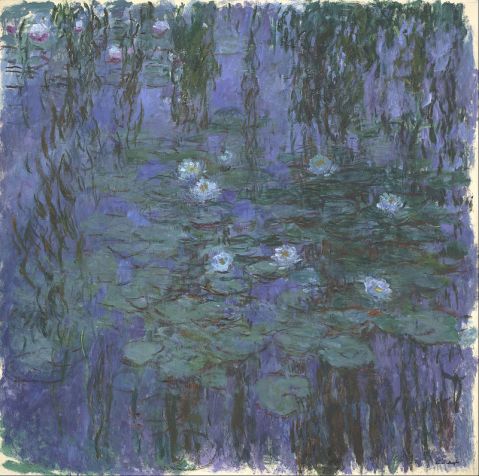

As with their lives in general, Manet and Monet were in common cause. By the time of their deaths, Monet would drift into near abstraction with his Water Lilies, while Manet created one of the most memorable of his works, A Bar at the Follies-Bergere (see below).

Monet, Blue Water Lilies, 1916-1919

Associations and Analogies

It was more than thirty years ago that I studied Impressionism at the University of Chicago, contemplating deeply the impact of Manet and Monet on the history of modernism. They would figure significantly in my Ph.D. comprehensive exams on the rise of modernism from Courbet (1850) to Kandinsky (1920). During this time I would contemplate many Impressionist paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago. One memorable evening at the Art Institute I led a tour sponsored by the Relief Society, an LDS women’s group in Hyde Park. Among them was Susan who soon would be studying for her Ph.D. in history at the University of Chicago. We spent quite a bit of time before Monet’s The Beach at Sainte-Adresse discussing broadly the social history of France through this work. My youthful enthusiasm has not been lost, but the emperor of all maladies now gives me a different reference point for contemplation.

Manet and Monet were disruptors, unwilling to accept the approaches of past generations. In his biography of cancer, The Emperor of All Maladies, Siddhartha Mukherjee recounts many of the heroes in the fight against cancer and their unwillingness to accept many of the approaches by past generations of cancer researchers. Yet as Mukherjee brilliantly notes, “The past is constantly conversing with the future” (466). In another place he says history repeats but science reverberates. The same can be said for artists and for art movements like Impressionism, seismic reverberations!

The Greek word for tumors is onkos, meaning mass or burden. My oncology team often refers to the tumor burden in my liver. What reverberates now in cancer research is the load built into our genome, what Mukherjee says “is the counterweight to our aspirations for immortality” (465). All those associated with the cancer wars are aware of this, but ironically immortality can come through the contributions to the quality of life by artists such as Manet and Monet, or the vast teams of researchers in what Mukherjee calls the “long arc of scientific discovery.” Without the millions of cancer patients who voluntarily enroll in experimental treatments, the arc of discovery would be even longer.

Manet, A Bar at the Folies Bergere (1882)

Manet’s A Bar at the Folies Bergere is a site for contemplating the legions of patients. Here he presents us with a double image of a woman who appears lost in self-reflection, while at the right of the painting she is conversing with a man who is none other than Manet. He is suffering from his own physical maladies, but clearly has empathy for this woman. Critic Ernest Chesnau summed up this magnificent painting in 1882, “His formula of art is very new, very personal, very piquant; it marks the artists’ conquest of the world of external phenomena, and it will not be lost on future generations.” Manet would die within the year.

What if we presume the woman is like the millions in a personal fight with cancer? How shall we describe her heroism, her grit, and her uniqueness among so many who have the same disease? If we could meet her, she might laugh and joke, playing her part like an accomplished actress on the stage Manet has constructed. Her illness tries to humiliate her, but there is no vengeance, only a determination to stay one step ahead of the disease. She is larger than life, and Manet has given her (and us the viewers) aspirations to keep inventing and reinventing ourselves for the twists and turns required by the emperor of all maladies. She urges us to live with dignity. As I said to Susan after our consultation this week, I am determined not to fritter away the life we have been given.

In solidarity,

Tom

New method discovered to reduce tumor burden

Oncologists are real people with a devotion to their work. One of those is Dr. Vincent Kunstwerk in New York. He worked his way through Yale Medical School in the 1960s as the department calligrapher, writing departmental invitations and signs. One of his favorite artists, Franz Kline, also has a calligraphic element to his work. In fact, Dr. Kunstwerk has discovered that sitting in front of a favorite work of art and talking to it like an old friend has a very calming effect. This can relieve tumor burden, he says. He also discovered, however, and wrote this up in JAMA, that the gaze process can have negative effects if you choose a work arbitrarily, like Ellsworth Kelly’s color field painting, and keep demanding of his inscrutable work “what does he mean”?

Kunstwerk has concluded through his rigorous observations that works like Franz Kiline’s 1950 painting were a perfect match for my circumstances. In fact I had written about a Kline painting in the permanent collection catalog of the Smart Museum of Chicago. My reflections as a young scholar now resonate differently with me as an older viewer with more life experiences: “Kline’s style in the early 1950s is characterized not only by the gradual transition from color to black and white, but by the use of drawings themselves as a reservoir of inspiration.” David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, A Guide to the Collection (1990), 143.

Dr. Kuntswerk felt there was something seriously missing from his theory–humor! He had his “Ah Ha” moment when he visited the archives of Dada Art in Zurich and discovered a quote from Hugo Ball & Emmy Hennings, founders of the movement in Switzerland. They were asked how Dada found fertile ground in Switzerland, and they both finished each other’s sentences by saying: “The Swiss flag is a big plus!”

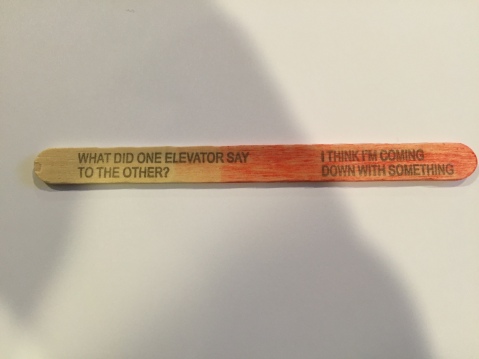

This shot of absurd humor inspired Dr. Kuntswerk to invest a substantial amount of his wealth in the Popsicle Company writing short riddles for the popsicle sticks. They have brought smiles to sufferers for generations, like the one pictured below:

Dr. Kunstwerk was born one day before me and received his first award for the corniest joke on the same day as his birthday, April 1. “Why didn’t the bloggers laugh at Tom’s blog? It didn’t make cents.”

Happy April Fools Day!

In solidarity,

Tom

Phlebotomists, Oncologists & Curators, Oh My!

Last week was a very revealing time in my team’s fight against my intrepid disease. First, I realized my fight has been prolonged for nearly four years. I am well known at the Huntsman Cancer Center. The valets greet me with “Welcome Back, Mr. Rugh—we love your car!” I am glad I can make their day with my reply, “Feel free to take it for a spin while I am working with my team inside.”

Vice President Biden making a stop at the Huntsman Center Center 2/26/2016 as leader of the national “Moon Shot” initiative against cancer. Courtesy Scott Howell.

Lauren and Emily are my expert phlebotomists. They take blood that measures the health of my liver, the chief marker being the bilirubin level. Emily, Lauren and I constitute a 90-second book group. We discuss our current reading and recommendations. Emily told me she was totally absorbed in E. H. Gombrich’s Little History of the World, which I had heartily recommended. She had taken it with her the previous weekend when she camped in a yurt in the Uintah Mountains.

In turn, I recommended When Breath Becomes Air, by Paul Kalanithi. I regard it as the best personal rumination of the fight against cancer, the nature of death, and the struggle to live by a young neurosurgeon. He ultimately lost this battle but his book is a lasting gift to all who are in this fight. Those on my phlebotomist team are true professionals who love their patients, and who lead very interesting lives.

Susan was not with me the next day for the consultation with Dr. Ward. He happily reported that my bilirubin had dropped even lower—to 2.4. Nevertheless, he is looking at potential treatments if the liver starts to deteriorate. It is a miracle that my tumor burden remains stable, that the markers for my liver health are gradually improving, and my blood clot appears to be dissolving.

I asked Dr. Ward how he approaches the issue of death and mortality with his patients. We talked at length about Paul Kalanithi’s book, and he concluded by saying that his belief in an afterlife has kept him going. I remarked that a scripture that fuels my optimism and fighting spirit is: “Lord I believe, help thou mine unbelief.” (Mark 9:24)

I told him fatigue was my biggest enemy right now, but he encouraged me to keep exercising and keep writing. He sent me a reassuring email later that day: “You are such a delight to talk with—a thoughtful intellect for which I have great admiration.”

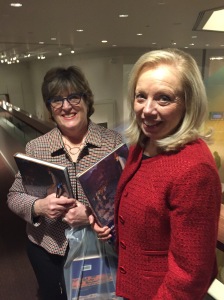

At the end of the week I accompanied Susan to a VIP tour and dinner for the opening of “Branding the American West: Painting and Films, 1900-1950” at the BYU Museum of Art. Led by Curator of American Art, Marian Wardle (see photo), Susan was one of the scholars involved in creating the exhibit, and contributed an essay to the exhibit catalog. This was a culmination of much effort for her and I was delighted to be her escort. There are some very significant art works in the exhibit by iconic American artists like Frederic Remington and Maynard Dixon, along with the featured paintings by the Taos School of Painters from the Stark Museum in Orange, Texas.

At the end of the week I accompanied Susan to a VIP tour and dinner for the opening of “Branding the American West: Painting and Films, 1900-1950” at the BYU Museum of Art. Led by Curator of American Art, Marian Wardle (see photo), Susan was one of the scholars involved in creating the exhibit, and contributed an essay to the exhibit catalog. This was a culmination of much effort for her and I was delighted to be her escort. There are some very significant art works in the exhibit by iconic American artists like Frederic Remington and Maynard Dixon, along with the featured paintings by the Taos School of Painters from the Stark Museum in Orange, Texas.

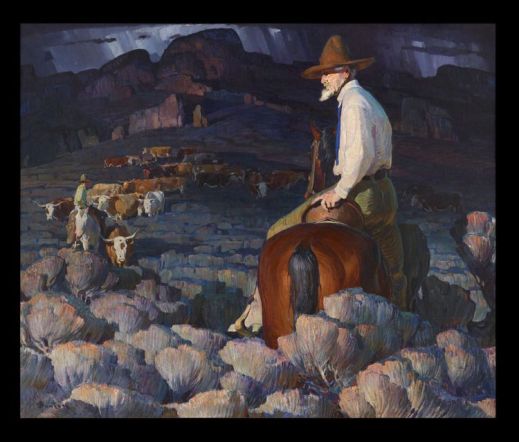

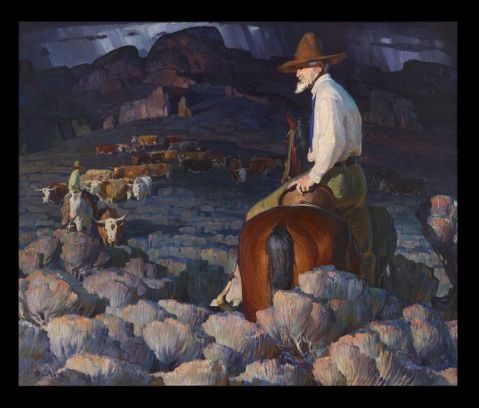

The signature painting of the exhibit is “The Cattle Buyer,” by William Herbert Dunton. This lush painting of cattle being herded across a darkened landscape with the sun breaking through the ominous clouds is a stunning tribute to the West that would soon be altered by the automobile.

William Herbert Dunton, The Cattle Buyer (1921)

This painting struck me as a metaphor for the current landscape of cancer care. Containing tumors is often a tactic that is hoped will turn cancer into a chronic illness. The goal is to put tumors in a docile state, like the cattle in the painting. Gradually the oncologist, like the cattle buyer, is finding ways to shrink the herd of tumors, lessening the burden on the land from the largest and hungriest cattle.

Even so, with the sunlight of optimism shining on the main figure, the dark sky underscores the difficulties and challenges of long-term struggle with the disease. Paradoxically, there is a newfound beauty in the landscape that makes the world worth fighting for. As I think of the cowboys who care for the herd, who brand the cattle and derive their identity from the landscape, I think of all the people in our life who care for us. Your support is felt each day as I gaze at my world, especially art works like “The Cattle Buyer.” I am so glad Susan and her colleagues have given us such a profound view of the American West that resonates in our hearts and minds.

Solidarity in running,

Tom

Man Up

My mother cried when I gave her a hug before getting on the plane for Alaska just days after finishing a year at Rio Hondo Community College in 1970. My cousin Stephen, a tall, jolly but tough guy who was the district attorney of Fairbanks, had arranged for me to fly to Anchorage. From there we flew on to Dillingham in his Cessna. He introduced me to Joe, a Native American/Alaskan (not an Eskimo) with whom I would fish King Salmon commercially with gill nets for the next few weeks. Joe was taciturn and liked his pancakes runny in the middle and burnt on the outside. We fished King Salmon with 100 fathoms of gill net drifting behind the 20-foot boat. I lost gloves and snaps on my weather gear in the whirling net streaming off the back of the boat. It was always very cold, no land in sight, and sand bars were real hazards.

My first near-death experience snuck up on us like a thief in the night. We awoke as dawn was breaking to a flashing depth meter. We were sitting on a sandbar; we had the real fear the boat would tip and we would freeze to death in the water. We drew in the net (with a gas powered drum on the back of the boat), pulled the motor up as high as possible and gunned it. Thick mud spit up behind us and the boat moved slowly off the sandbar. We celebrated with a can of Dinty More beef stew and a Dr. Pepper. Joe laughed as I heaved the stew overboard, but the Dr. Pepper settled my stomach that was constantly plagued by seasickness. To this day I can’t even look at canned stew at the grocery store without a queasy feeling.

I was lucky to have this job. Stephen offered it to me because my Dad had helped him with summer jobs to get through law school at Berkeley. He offered me $750 per week or a third of the profit, but added that the fish might not run and there could possibly be no profit. I took the $750 per week. (This would be a major funding source for my two year LDS mission.) When I returned in July I tried to put the memory of difficult events behind me, especially with my sister Barbara’s wedding at hand. Nevertheless as I sat at the small ceremony next to my Aunt Katherine, she was appalled when I reached up to my ear and dislodged a large salmon scale that fell into my lap!

Even though I loved summers at the ocean, playing volleyball, body surfing, and driving my 305 Honda on the small streets of Corona Del Mar wearing just flip flops and a bathing suit (my track shorts)—it was different in Alaska, where it was cold most of the time. As a break from eating canned beef stew on the boat, we occasionally ate meals in Dillingham, Naknek or Igiugig. The meal was very hurried at long tables with other fishermen, and NO small talk! The smell of processing fish in the canneries of these small ocean side outposts reminded me of accompanying my Dad to the end of the long pier at Huntington Beach when I was a boy. Men were lined along the end of the pier pulling all manner of fish on deck. I watched in amazement as creatures like Sting Rays flipped and flopped before being subdued. All this was groundwork before leaving “Sunny Southern Cal” for the vast unknown of Alaska, what Romantic poets called the circuitous journey of life that starts in the salty water of the womb.

I am certain my mother knew this was the beginning of my permanent separation from the nest and launch of the journey to becoming a man. Poet Billy Collins wrote “Lanyard” about a boy who makes his mother a lanyard at camp and considers it an even exchange for his mother’s nurturing and devotion. Unlike a lanyard, my gift was a sm all replica of the Pieta I brought my Mother from the 1964 New York World’s Fair. The day at the fair was a prelude to the Boy Scout Jamboree at Valley Forge. When I returned to LA from the Jamboree my Mother asked me what I remembered most from my trip to Pennsylvania. “I can’t believe the grass grows right up to the edge of the road!” was my immediate reply. Like the famous scene from the movie “Lawrence of Arabia” where the shadows from the trees flicker on the road as Peter O’Toole speeds along on his motorcycle, I was mesmerized sitting at the window of the bus watching the grass touch the road over and over again. As was true for many teenagers at 13, my mother and dad helped me discover my world.

all replica of the Pieta I brought my Mother from the 1964 New York World’s Fair. The day at the fair was a prelude to the Boy Scout Jamboree at Valley Forge. When I returned to LA from the Jamboree my Mother asked me what I remembered most from my trip to Pennsylvania. “I can’t believe the grass grows right up to the edge of the road!” was my immediate reply. Like the famous scene from the movie “Lawrence of Arabia” where the shadows from the trees flicker on the road as Peter O’Toole speeds along on his motorcycle, I was mesmerized sitting at the window of the bus watching the grass touch the road over and over again. As was true for many teenagers at 13, my mother and dad helped me discover my world.

The first night in Alaska I bunked on the boat that was tied to a pylon on the dock. This allowed the boat to turn at a 45-degree angle when the tide rolled out between 10 pm and midnight. But it left me clinging to the top bunk so I wouldn’t slide off! At about 2 am the tide returned and the boat slowly straightened up, but not without a constant creaking like an old garage door opening. I consoled my sleep deprived self knowing I was making $750 per week.

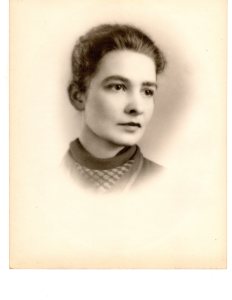

As I pondered the days ahead I was comforted with memories of Mother. She helped me with my toughest classes in high school, math and Latin. She co-signed for the loan on my 1965 VW Beatle, the same model, year and color as the VW on the cover of the Abbey Road.

She comforted me when I was sick—sometimes my own doing. In 1968 I was invited to several private parties of my classmates, including an unforgettable pool party that included cases of champagne. I drank the bubbly like I would down an Orange Crush. My friend Brian drove me home and left me to my own devices to get up the driveway and into the house. As I began to climb the six steps up to our porch, I veered off and fell into the bushes. I moaned until Mother ran out and with urgency asked, “Tommy, are you alright?” She and my Dad got me to my bed where I suffered from a hangover the next day that was greater punishment than anything my parents could say or do.

My first two years of high school were a disappointment to Mother. I had become a slacker. Instead of doing my homework after school, I played pool in our den. Instead of buckling down, I spent endless hours working on my stamp collection, which I spread all over our pool table. Instead of memorizing the poem “If” by Rudyard Kipling like my Dad had done in high school, I was listening to “Light My Fire” by the Doors. My academic fire was not yet lit.

In the evenings Mother taught me to play chess, after her relaxing moment smoking a Lucky Strike. I later learned that when my parents met at Ohio State in the library, my Dad suggested they go outside and have a “Lucky” to get to know each other better. It was not just a coincidence that women like my Mother smoked Lucky Strike cigarettes. On Easter 1928 women marched down Park Avenue with cigarettes in hand they called “torches of freedom.” American Tobacco Company, the maker of Lucky Strikes, had commissioned Edward Bernaise, a marketing genius, to help the company’s Lucky Strikes become a common commodity of consumption among women.

He connected the liberation of women to consuming Lucky Strikes. He even got the support of the fashion industry to design clothes the color of the Lucky Strike label. As a graduate of Bryn Mawr, my Mother was an archetype of the strong self-confident liberated woman, the ideal target of Bernaise and his cohort. No wonder my Mother was loyal to the Lucky Strike brand for the rest of her life. There were times when I was tempted to take one of Mother’s Lucky Strikes and try smoking it in our back yard. It was never a pleasurable experience, but at least I had tried it.

By the time I was a junior on the track team, my competitive spirit was sparked. My coach, Tom Putnam, encouraged me to develop as a sprinter. When I asked him what shoe I should buy he said: “Go to the shoe store and check for the shoe box that says you will run fast in their shoe–buy that.” Adidas passed the test. I won several 100 and 220 yard dashes, and with my teammates became one of the fastest 4 X 100 yard relay teams, winning medals in my senior year at the top Southern California invitational meets: the Mt. Sac Relays and the Rose Bowl Games. I wanted to win as a sprinter, and achieve in the classroom as well.

So I buckled down and did very well the last two years of high school. But I did not have the GPA to get into a four-year college, so in the fall I enrolled at Rio Hondo Community College. I loved my classes and held a nearly straight “A” average. With my safe return from Alaska, and respectable grades, my parents’ endless effort raising me from boyhood to manhood was validated.

My parents knew I was headed to new intellectual territory when I took an interest in the German moral philosophers. This pleased my mother who was a German major in college and studied in Germany during her years at Bryn Mawr. Dad would listen with interest as I read him papers I had written for class. One evening while he was taking his bubble bath, I sat on the toilet seat and read him a ten-page paper on whether Kant’s”a priori” judgements were possible. When I finished I asked him what he thought; he replied with a twinkle in his eye, “I Kant understand it.”

In the next several years I would try to make sense of the spiritual and political events of my life. More to come!

Faith in running,

Tom